Technique First: Reclaiming the Foundation of Music Education in 2026

Music education in 2026 exists in a paradoxical moment. Never before have students had such immediate access to music, technology, and performance opportunities, and yet many programs struggle to produce musicians with consistent tone, rhythmic stability, or technical confidence. Ensembles may sound active and visually impressive, but underneath the surface there is often a lack of fundamental control. This disconnect reveals a deeper issue: many programs have prioritized output over infrastructure, favoring frequent performances and quick results at the expense of systematic technical development.

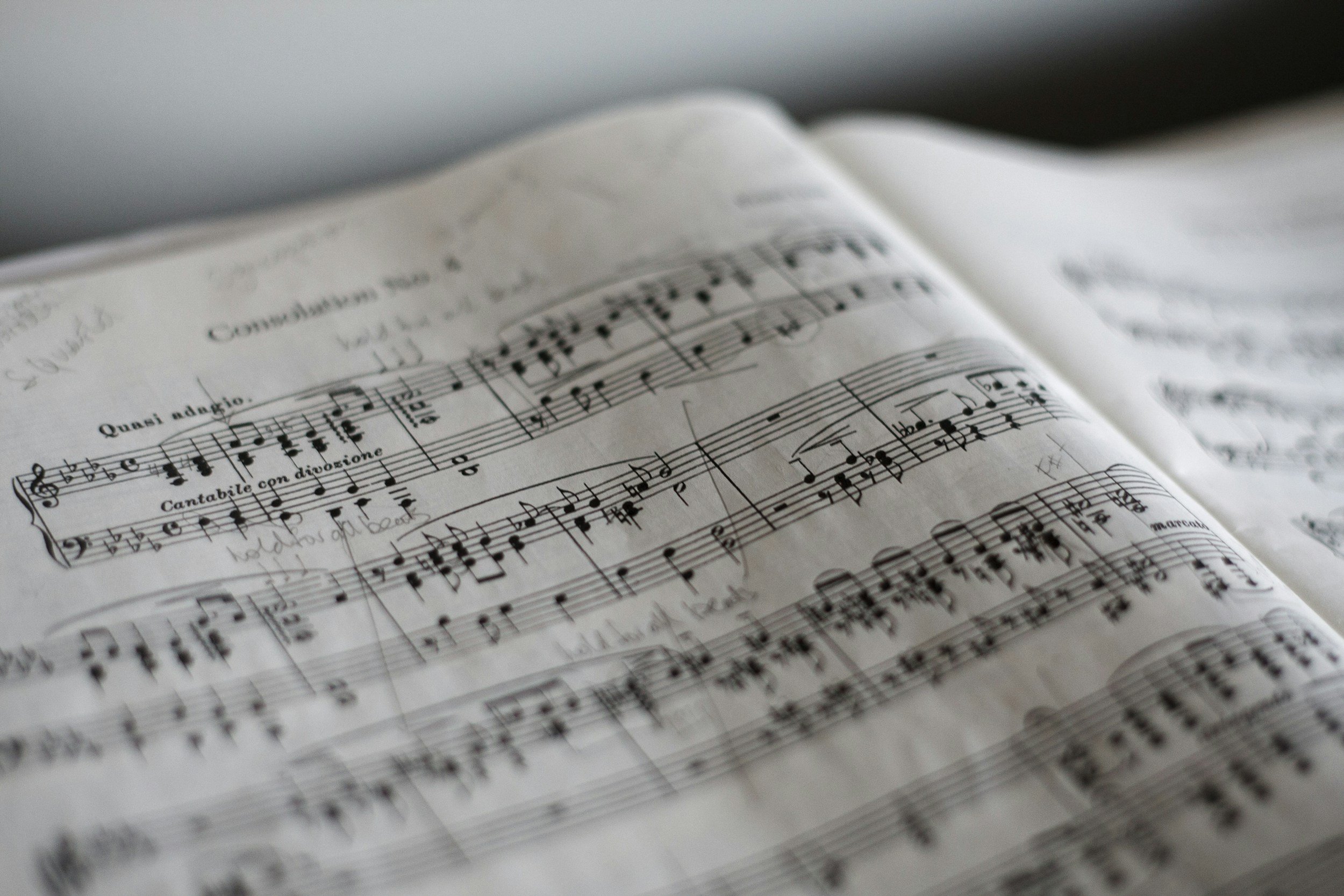

Technique is not a preliminary hurdle to be cleared before “real music” begins; it is the framework that allows musical understanding to manifest in sound. Breath support, embouchure formation, vocal function, hand position, posture, articulation, and rhythmic literacy are not ancillary skills—they are the means by which musical intention becomes audible. When these elements are inconsistently taught or loosely defined, students are left guessing how to improve, relying on external correction rather than internal awareness.

In many modern programs, technical deficiencies are unintentionally hidden by well-meaning shortcuts. Simplified repertoire reduces demands on range and articulation, dense scoring masks individual tone issues, and amplification or digital correction compensates for weak production. While these strategies may increase participation or short-term success, they often prevent students from developing endurance, intonation control, and the ability to sustain sound with consistency. Over time, students become dependent on the ensemble or the technology rather than confident in their own musicianship.

This drift toward low-technique models is frequently justified by claims of accessibility or stylistic relevance. However, technique is not genre-bound. Whether students engage in classical literature, jazz improvisation, marching arts, worship music, or commercial styles, they rely on the same physical and cognitive skills. A jazz saxophonist’s command of tone and time, a vocalist’s breath management across extended phrases, or a percussionist’s control of stroke and subdivision all emerge from disciplined technical training. Without it, stylistic exploration becomes superficial rather than authentic.

The role of the educator is central in this process. Programs inevitably mirror the technical priorities of their teachers. When educators model vague language, inconsistent fundamentals, or minimal personal practice, students internalize those standards. Conversely, when teachers demonstrate refined tone, sing or play with accuracy, and speak precisely about sound and process, students learn to listen critically and take ownership of their development. In 2026, the expectation must be that music educators remain active learners—engaged in personal practice, pedagogical study, and reflective teaching—so their instruction remains grounded in competence rather than habit.

Rebuilding programs around technique does not require abandoning creativity or student engagement. Instead, it demands intentional structure. Daily fundamentals become the shared vocabulary of the ensemble, allowing rehearsals to move efficiently from sound production to musical expression. Scales, long tones, vocalises, rhythmic studies, and articulation patterns cease to be warm-ups and instead function as diagnostic tools that inform repertoire choices and rehearsal strategies. When technique is embedded consistently, students progress more quickly, repertoire becomes more accessible, and ensemble sound matures organically.

A defining outcome of technique-centered instruction is student independence. Students learn to identify pitch inconsistencies, rhythmic instability, balance issues, and tone problems without waiting for correction. They develop the ability to practice with purpose, adjusting physical habits and musical choices based on clear criteria. This independence is not accidental; it is cultivated through repetition, precise feedback, and a shared understanding of what quality sounds and feels like. Programs that neglect technique rarely produce self-sufficient musicians, regardless of how many performances they schedule.

Ultimately, the measure of a successful music program is not the number of concerts presented or accolades received, but the durability of the musicians it produces. Students grounded in technique can adapt to new ensembles, styles, and expectations long after their formal education ends. Those without it often struggle beyond the safety net of structured programs. If music education is to maintain credibility and relevance in 2026 and beyond, educators must resist the pressure to chase trends that value immediacy over mastery.

Technique is not a limitation on expression; it is the condition that makes expression possible. By reclaiming a technique-first philosophy, music educators can build programs that are inclusive yet rigorous, modern yet grounded, and capable of developing musicians who are not only active participants, but confident, independent artists.